Against specialization

Why artists and cultural workers should embrace generalization in an era of constant crisis.

Remember that saying “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket?” That tried and true advice growing up was phenomenal, yet so many of us in the creative economy struggle to transition from one role to another. Artists question if they can afford the time to work on their neighborhood projects when others tell them it’s better to stick to their solitary studio practice. Museum workers believe their skills can’t transfer (when they definitely do). Open positions continue to hire algorithmic exact matches, only to see burnout, turnaround, and dissatisfaction at a nearly all-time highs. Somehow, while we want change, yearn for something else, we end up turning our backs from it. The eggs stay in the same basket. Why?

I think a root cause is the creative economy’s demand for specialization. Doing one thing extraordinarily well makes workers efficient and profitable, but it leaves us susceptible to job insecurity and alienation. The alternative is to reposition our work as doing many things pretty well—and I’m already witnessing how this generalized approach leads to professional and psychological resiliency.

Yes, there is an alternative

Dario Gentili’s The Age of Precarity: Endless Crisis as an Art of Government is a Naomi Klein-adjacent articulation that unpacks why neoliberal governments use “crisis” as a tool (and art form) to pass de-regulation legislation (see: The Iraq Invasion that miraculously reigned in gas; The Great Recession that gave bailouts to CEOs; COVID-19 translating to big pharma making millions from the U.S. government; “bankrupt” Michigan cities led to polluting its own citizens).

Somehow, the more crises we have, the stronger and wealthier the rich get. Somehow, the more crises we have, the more everyone else sees their pay cut, their grocery prices doubled, their homes evicted (if not destroyed by wildfires and floods), their friends pass of COVID, and the blame placed somehow on us all… and not on the people exploiting the entire planet in the first place.

Part of me believes we accept this narrative because we’re too far down the specialized path—cultivating a “stay in your lane, just work harder” mindset. We’re tucked away in small pockets of friends, in our emails, checking our to-do lists at work, toiling at our little tasks in our little houses just to stay #sane. Specialization has made us believe that if we just do our one thing well (make the best paintings, write the best press release, talk to the same people at work), we’ll get by. Heaven forbid we apply our skillsets to communities and causes outside of our resume. Heaven forbid we find solidarity across industries, classes, and geographies. Because if heaven didn’t forbid it, we’d find that the overwhelming majority of working- and middle-class people experience the same day-to-day struggles and would likely come together to solve our collective problems.

Nature’s point of view

One look at nature will demonstrate how generalization benefits individual species and their ecosystems. I revisited Minute Earth’s video on ecological redundancy (translation: generalization!), and there’s a powerful line halfway through:

On the ecosystem level, an occasional extinction isn’t always that big of a deal. That’s because in some ecosystems, several very different organisms fill similar roles…. Just like when a train’s brakes fail and the backups can divert disaster, when, say, a beetle species goes extinct, other decomposers can keep on breaking down dead stuff.

Here, redundancy builds resiliency in a system that needs certain processes to continue. Take a human example: what if, in the near future, one city’s monopolized garbage pickup company went bankrupt and fired its staff? The entire city’s population would have a few days (months…?) of garbage, piling up outside our homes. But: if that city already had local sites to drop off recycling and compost, our garbage piles would shrink in size. Hell, having neighborhood or regional garbage companies could translate to hiring those fired and keep systems running. This “redundancy” is actually the ability for others to perform similar roles, covering in case of an outage.

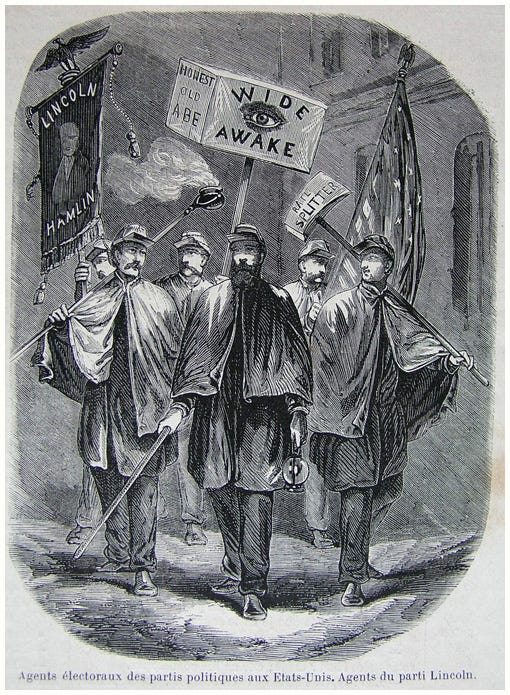

Take the Wide Awakes—or the job market

My own case in point was working with the Wide Awakes in 2020 to match a $250,000 gift for 14 nationwide civic participation initiatives right before the 2020 election. The Wide Awakes are an intergenerational group of artists, activists, and thinkers who plan and execute their projects primarily through a decentralized decision-making process. They not only reinvigorate the history of the 1860s Wide Awakes—who helped get Abraham Lincoln elected via speeches, actions, and marches of black, brown, and white abolitionists—but they are also artists using their skillsets generally, not specifically.

Artists know how to get people to pay attention. The Wide Awakes used their artistry not for a white walled gallery show, but for direct civic actions. It took borrowing from the fields of activism, communications, PR, event management, and campaigning. They widened (generalized) their skillset, raised and distributed a total of $508,793 a month before November 2020, and proved to be incredibly effective at spreading their message.

We can also take a more literal approach by reviewing trends in the creative economy job market. Employers and recruiters *think* they need to find someone with exact, direct, specific experience doing the job’s responsibilities. I’ve witnessed this firsthand after applying to 96 positions the last two years. Of the six I’ve interviewed for (three nonprofits and three for-profits), the jobs went to those with, on average, twice the experience listed in the job description and one. (AKA: 3-5 years experience actually means whoever has the most). They often were in past roles (one, if not two), with the exact same job titles.

Of these six roles, four of them opened back up in just one year of hiring.

This means we can safely conclude someone with a perceived “exact” match was actually not a match after all. We see this echoed across experience levels, too: a curator must become a museum director. A development manager must come from development. An entry position requires a masters’ degree. (Sounds like neoliberal “there is no alternative” to me.)

That’s why I think employers across the creative economy don’t actually need specialized skillsets, they need general skillsets. A culturally abundant staff with a wide gamut of lived experiences across titles and industries will better guarantee resilience, and survival, in an era of constant crisis, just like nature.

I’ve also found at my own consultancy that when I hire generalists, they offer new and fresh ideas. When under pressure, they zoom out, see the larger picture, and place problems into perspective. And if I throw them new tasks, they ask functional questions about how to do it—and why we’re doing it—which forces me to better articulate my asks and strategies. That two-directional feedback leads to stronger work, hands down.

General Forever

If we’re going to build anti- or post-capitalist support structures in this era of endless crisis, the creative economy can’t rely on specialization. It makes us too susceptible to abrupt changes and too wary of one another.

Think about the last time you volunteered or showed up to a mutual aid event. Remember when someone asked you to do something you didn’t really know how to? Remember when you actually did it pretty well, minus a spill here and there? And remember when you left feeling so good, so part of something larger? That’s the energy I want to nudge us toward.

Generalization won’t solve our global crises (that may take a revolution, eep!), but it might just keep us resilient and ready to face crises together instead of apart. Let’s be the beetles, the bugs, and the mushrooms together, because if one of us needs to take a break, the rest can fill in.

If you’re a recruiter or employer, I’d love to hear your perspective (or any data sets) that supports or contradicts my thoughts. And if you’re pro-generalist like me, how have you also seen this framework… work?

Thanks to Izzy Dow, Crystal Gause, Tessa Beck, and Patton Hindle for their thoughts, suggestions, and unwavering support of the work I do. Love y’all.

love all of the outside links! the big picture is big

aigcontemporary@gmail.com